#BlackLivesMatter and (Mostly) White Churches (Part 2)

For part 1 in this series, click here.

—

The Scapegoat(s)

“… it is better for you that one man die for the people than that the whole nation perish.” … So from that day on they plotted to take his life.

(John 11:50-53)

Buried deeply in our religious memory is a ritual we would prefer to forget. Forged in a world where violence begat violence (think “an eye for an eye”), we needed something to break this bloody cycle. A final act of violence to make peace. We needed the scapegoat.

The term is not unusual to us. A scapegoat is someone who we blame for our own failures.

Perhaps the custom of scapegoating was inevitable.

Just the other night, on a church playground, a three-year-old boy grabbed a little girl by the arm and threw her to the ground violently. She was playing with a toy he had abandoned earlier. But when his parents asked why he did it, there was no hesitation—“She poked me in the eye.”

She didn’t poke him. They had watched it all unfold.

Even at age three, we convince ourselves that by blaming our sin on someone else, we might be redeemed. We need the scapegoat.

This tendency is not unique to individuals. In some of the earliest societies on record, we see the scapegoat process turned into a corporate ritual. Societies unable to apply the brakes on violence in their midst had to develop some way to stop their momentum, lest they destroy themselves. So they, corporately, did what was instinctual—blamed someone else.

The easiest to blame were always the defenseless: the intellectually impaired, the weak, the eccentrics, the foreigners. In order to stop any more mayhem, the community would accept one more act of madness. Ritually heaping their sins onto the scapegoat, the entire village would push the selected person to the edge of a cliff, form a half-circle around him or her, and in an act of “purification,” stone the scapegoat to death. They breathed a sigh of relief. All was made right. Their sins forgotten.

Israel amends the practice slightly, selecting instead of a human victim, a goat. Thus, the origin of the term.

To purify the people, Aaron is told to:

Lay both hands on the head of the live goat and confess over it all the wickedness and rebellion of the Israelites—all their sins—and put them on the goat’s head. He shall send the goat away into the wilderness in the care of someone appointed for the task. The goat will carry on itself all their sins to a remote place; and the man shall release it in the wilderness. (Lev 16:21-22)

Again, all is made right. Sins forgotten.

The life and death of Jesus now come into sharper focus. When John sees Jesus and declares, “Look, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sin of the world!” (John 1:29), we now recognize this is not simply a metaphor for Jesus’ unblemished “lamb-like” character, but a stark prophecy about how and why Jesus’ life will ultimately end. He will become the scapegoat, who “suffered outside the city… bearing the disgrace” the people can’t bear themselves any longer (Heb 13:12-13).

Out of sight, out of mind.

So, the high priest Caiaphas is devilishly onto something when he reminds his people, “… it is better for you that one man die for the people than that the whole nation perish” (John 11:50). Rather than own up to their collective sin, their complicity with the violence of Rome, and their part in the creation and propagation of a legal system that was itself violent, he knew they could just blame someone else.

Calming everyone down, Caiaphas reminds them of the way things have always worked. If you blame someone else, and everyone joins in, their execution is like a healing balm on a violent nation. Uniting everyone (11:51-52), even if in ignorance.

Only, the death of Jesus does the opposite. Because unlike similar rituals throughout history, where the scapegoat is guilty simply because they are corporately blamed, the followers of Jesus were unwillingly to accept his guilt. Instead, they went to great lengths to prove he was innocent, and in so doing bring the scapegoating ritual to its knees. The wrongful death of Jesus, unlike any time before it in history, exposes and indicts the violence of the world and its dependence on scapegoating.

An innocent man was killed, and that’s not okay.

In Jesus’ kingdom, where he makes peace, preaches peace, and even is peace (Eph 2:14-18), violence is treason. Treason that cannot be undone by some additional, and fictionally “final,” act of redemptive violence. Blaming the innocent and defenseless for the sins of others or our own is intolerable. Scapegoating cannot exist within the Kingdom of God.

It is not okay to blame the innocent.

It is not okay to heap upon them the violent sins of others. It is not okay to heap upon them our own violence. It is not okay to force them outside the city to suffer and bear our disgrace.

That’s scapegoating. And scapegoating is treason. God’s kingdom will not stomach it.

What does this have to do with talking about race in a (mostly) white church?

The answer is simple and tragic. Many white church-goers fail to acknowledge the realities of systemic racism and white privilege today. Taken by themselves, these ignorant lapses would be lamentable. However, the lapses compound to permit a terrifying amount of grossly misplaced blame, or in other words, scapegoating.

It sounds like this: “Blacks just have a culture problem.” “If they would just make good decisions….” “If they just worked harder…” “If they just obeyed the officer…”

Some Christians from (mostly) white churches say these very things. You’ve heard them.

Those accusations are not only wrong, they are badly misplaced. We can diagnose this as a case of “plank-itis.” You know, trying to remove a spec from someone’s eye when you’ve got a plank in yours (I think Jesus said something about this chronic condition). In this case, the plank in our eye—the sin in need of atonement—is the systemic disadvantaging of black lives over centuries.

If we shift that sin onto the victims of it, then we have scapegoated the innocent.

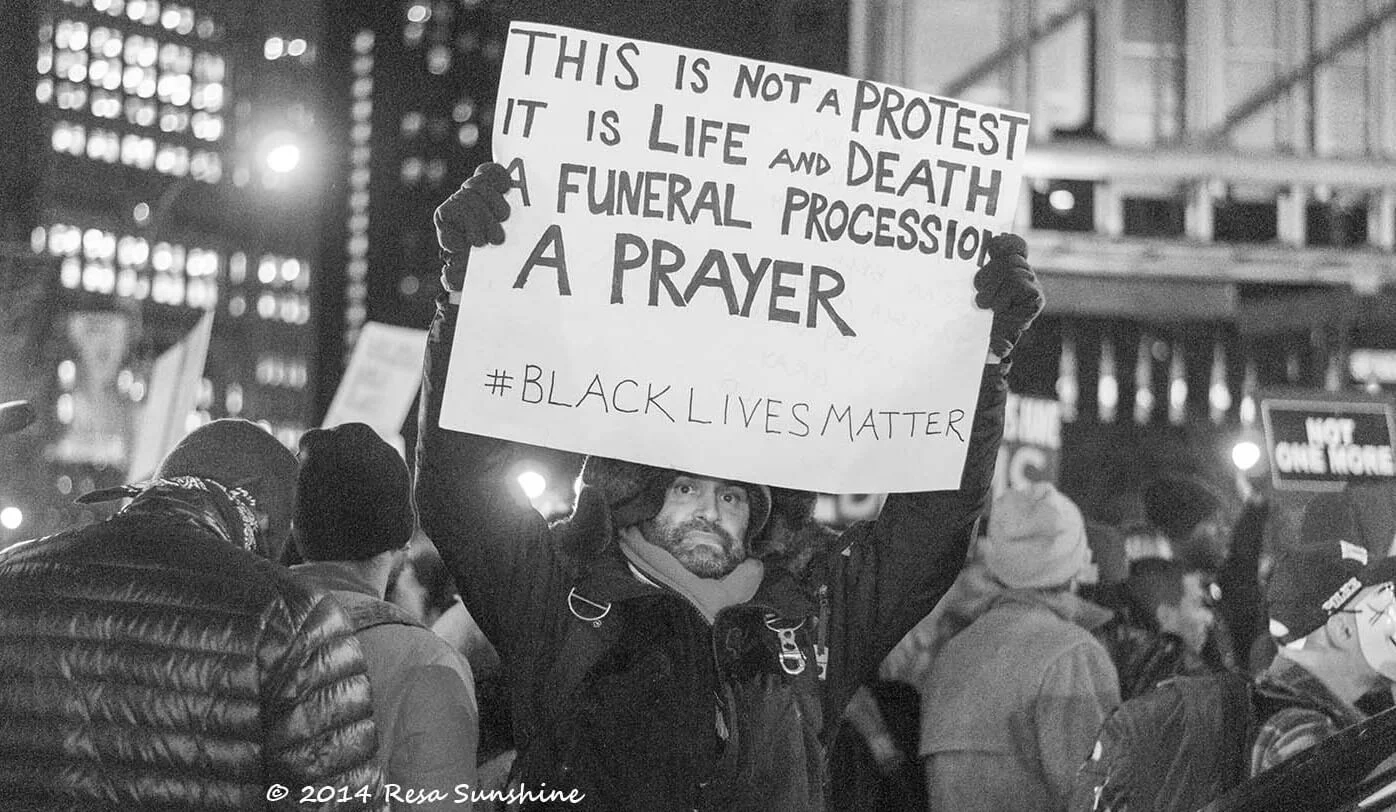

That’s why we need to talk about #BlackLivesMatter in (mostly) white churches.

If not, black lives won’t matter.

—

Eric will be leading a session at Lipscomb’s Summer Celebration in June 2016, entitled “Talking about Race in (Mostly) White Churches.” There he will outline the curriculum Highland has used to discuss race, racism, and biblical justice.

Header image by Elvert Barnes. Taken June 19, 2015. Juneteenth Inter-Faith Prayer Vigil for Emmanuel AME Church at the African American Civil War Memorial in Washington, D.C. Retrieved from flickr.com. Some rights reserved.