My Enemies Have Stories

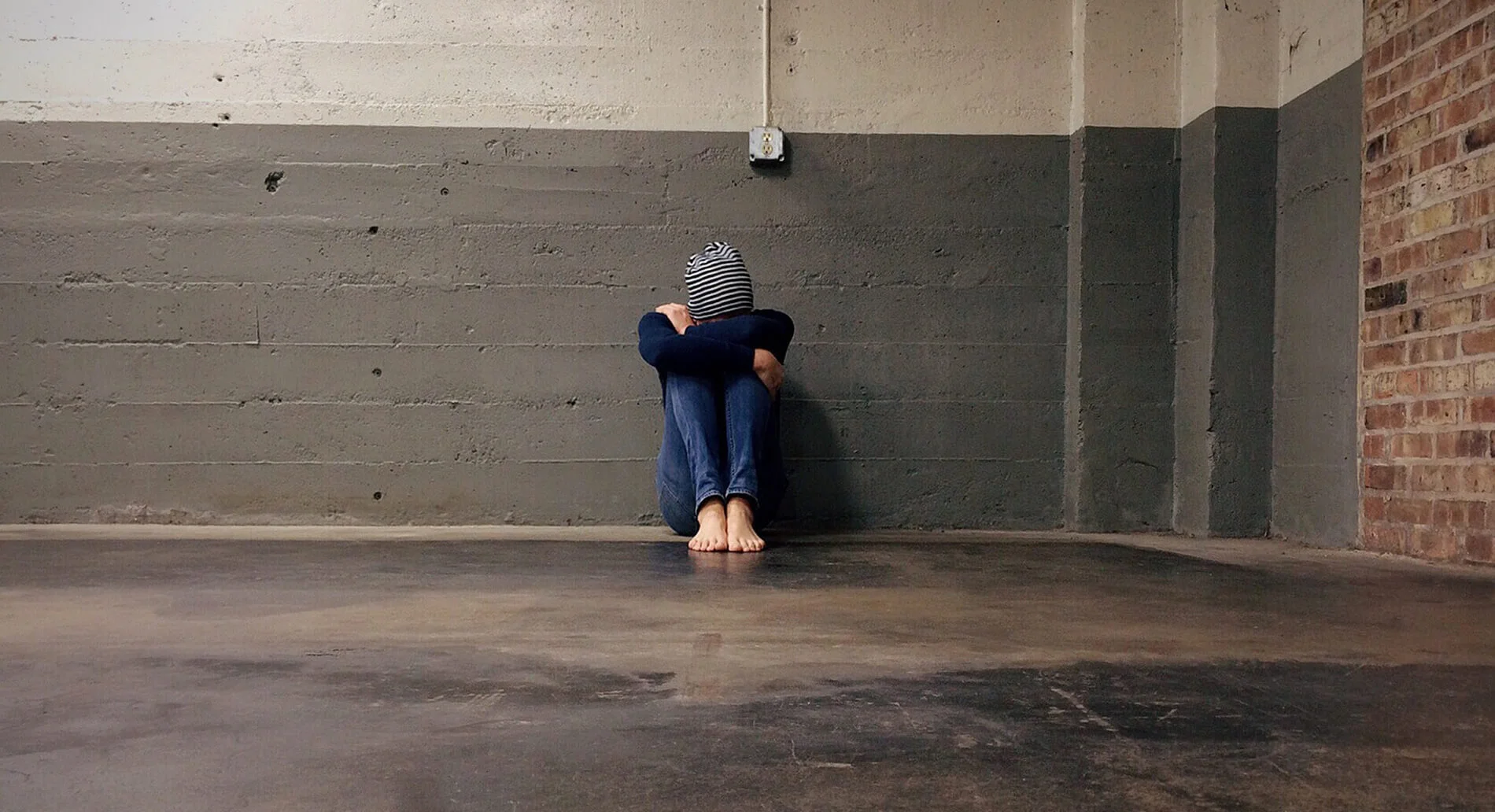

Enemies take on many forms, ranging in proximity to your present life, and making grand entrances and exits throughout your life story. People often become our enemies when they irreparably (and perhaps intentionally) wound us, leaving us to pick up the pieces of the fallout. There are also those enemies who cause harm in less personal ways, perhaps by inflicting harm upon our communities or our world. However, my greatest difficulty is with my personal enemies—those individuals whose faces are burned into my mind after very personal attacks, the ones whose names raise the hair on the back of my neck and instantaneously cause my blood to boil. I have approximately five enemies. I know it sounds crazy that I have counted them, but that’s how aware I am of how much they hurt me. If I allowed myself, I could sit and stew over the ways they have wronged me and my loved ones for hours on end. I have allowed them to ruin more days than I would like to admit. My inability (or unwillingness, rather) to let them go often makes me feel childish and small. And you know what is particularly sad about my relationship with my enemies? Out of the five, I have only seen one of them in the past five years. One of them I haven’t seen in twelve years, and another one I have actually never met.

I made this confession to my mom over the holidays. We found ourselves sitting out on the porch swing on an unusually warm evening, talking honestly about our enemies as we watched the sun set. Before I knew it, my confession came tumbling out: I don’t know how to forgive them. I do not deny the command of Christ to love my enemies and pray for my persecutors, I just simply don’t know how to love them and pray for them. My mother, a woman of deep conviction, was quiet for a moment. Then she responded, “I have my enemies too, you know. It’s not easy. I don’t know how long the journey to forgiveness takes, but we have to keep trying. It is the way of Christ.”

I know she is right. And chances are if you’re being honest with yourself, you have enemies you need to forgive too. Jesus didn’t pretend like enemies are a nonissue for his followers; he acknowledged the struggle in his insistent teaching. Yet his instruction to love them is often lost in our internal seas of unresolved bitterness, or our storehouses of vindictive aggression. So how do we find healing, and how do we forgive?

I won’t pretend to have all the answers, but I believe I have stumbled upon one piece of this puzzle that is worth sharing with you. In the cases of most of my enemies, I feel as though they took something from me that I can never get back. They robbed me of my time, joy, safety, and in some cases, my sense of self. Much of my anger towards them stems from a realization that the wrong they inflicted cannot necessarily be undone—it’s a permanent part of my story. Sometimes I wish parts of my story were brighter, or more reasonable, but they never will be.

So perhaps the first step in loving and forgiving my enemies is in my own reconciliation—the reconciliation of all parts of my story. When we take a step back and assess where we’ve been and where we are going, how do the most painful parts of our stories factor into the remainder of our lives? Well, first of all, the most painful parts offer some contrast, making the gifts of life shine brighter. Second, seasons of attack challenge us to grow stronger in our attempt to survive. And perhaps most importantly of all, life’s wounds teach us more about the human experience and enable us to walk with others who suffer similar situations. So yes, my enemies altered my story, but if I really believe in the reconciliation of all things, I must believe that God is helping me to gather all the pieces of my life to create something beautiful and good.

The not-always-so-obvious flipside of this belief is that perhaps my enemies are also being reconciled. Maybe they inflicted pain and wreaked havoc in their darkest season. And perhaps they woke up the next day, or maybe many years later, to recognize what harm they had caused. Meanwhile, God looked upon that child who was also made in the Imago Dei, and extended reconciliation for their story. Would I dare to wish for their condemnation instead of reconciliation? Would I hope that God overlooked their pain while tending to my pain? Would I expect God to declare somebody a lost cause, while pulling me from the pit of despair? If so, I have sorely misunderstood the love of God.

I do not possess the power to forgive my enemies in the same way that God does, but maybe in recognizing the ongoing reconciliation of my own life, I will carry a deeper respect for God’s reconciling of my enemy. In turn, I will even hope for their reconciliation. In my hope, I find a willingness to pray for my enemy, and in my prayer, I am drawn into the all-encompassing love of God for my enemy. I find that this process is not a one-off event, or a cure-all of any sort. Rather, it is a journey of continuous conviction, and a striving to understand the heart of God.

These thoughts come to the forefront this week upon the recent sentencing of murderer Dylann Roof to death, following his racist rampage in Charleston. While many celebrated the dealing of justice, I also witnessed an unusual sadness among many Christian communities, including some of those who were most directly affected by Dylann’s actions. I heard Christians acknowledge pain, condemn violence, honor life, and in turn, long for a different outcome for Dylann. Many pleaded, not for violence to be returned to the perpetrator, but for an opportunity for Dylann’s story to find some kind of reconciliation. What radical faith is this, that would long for the reconciliation of a murderer? What absurd belief would cause us to love those who hate us? It is the radical and whole-hearted hope that we too are being redeemed, and that our stories are not yet complete.